Buying Mice

Before you set out to buy your mice, take stock of what purpose they’ll have for you. Do you want a few pets? Mice to breed? Show stock? Each of these goals will have very different needs.

While anyone out to purchase mice would do best to contact a private breeder, most breeders specialize in either pet mice or show mice. If you intend to breed, that’s important information that can help your breeder find the best mice for you. If you want to show mice, getting in touch with other show breeders over facebook or forums can help. You can then find what variety you’re most interested in, and help you find breeders. If you’re looking for friendly pet mice, the breeder can tell you which lines are the best for that, too.

Once you’ve found breeders in your area, contacting them over email or through their webpages is a great way to get in touch. Let them know what kind of mice you’re looking for and ask whether they can help. If they can, you’ll want to ask about any health problems in the line, or any other peculiarities, since all mice are different. The breeder is an excellent resource for information about the health, temperament, keeping, and breeding of your mice. In general, female mice (called does) do best in social groups, while male mice (called bucks) do best alone.

Transport

Bringing mice home is best done in a container with sufficient ventilation, no water bottle, some bedding, and which is not made of cardboard. Tupperware with no holes in it can easily suffocate a mouse during the drive, and a cardboard box is no match against a mouse with five minutes and razor-sharp teeth. Water bottles tend to leak in the car, so shorter drives usually are fine with no water. For longer drives, a section of a cucumber or celery provides moisture that will not leak out onto the bedding. If you have no other mice, the mouse’s permanent home is a fine transport cage, as would be a small Kritter Keeper or similar plastic transport carrier.

Enclosure

Before you bring new mice home, make sure you have their new home ready. Groups of females up to around 4 can be kept in 10 gallon aquariums with mesh lids, or larger groups in a 20 gallon long. Solid-walled caging like aquariums need to be no taller than 12” in order for the mesh lid to provide sufficient air circulation.

Many mouse owners use homemade cages made from large Rubbermaid-type tubs, adding fine wire mesh to the sides and lid for ventilation.

Bar cages need to have very close bars, as a mouse can easily escape if there is even one gap large enough for their skull to fit through. Quarter-inch bar spacing is usually sufficient for adults, though baby mice may be able to escape. Bar cages are not recommended for maternity housing for this reason.

Hamster-type cages of solid plastic are generally considered very bad for mice, as they are chewable, hard to clean, and have insufficient ventilation.

Bedding

The enclosure needs some bedding in it, too. Aspen is a fairly safe choice in wood shavings, providing a fluffy material without the dangerous oils in pine and cedar. Sanichips are a very finely cut aspen flake that dries more quickly but does not have the fluffy quality. Other bedding options include paper beddings like Carefresh or Soft n Cozy, or pelletized beddings made of paper or alfalfa. Avoid softwood, conifer, and cedar bedding. These have been proven to be dangerous to small animals.

Each of these has its advantages and disadvantages, with some cheaper, some keeping the cage drier, and others helping to minimize odor. How frequently the bedding needs to be changed will depend on the number of mice for the space, which bedding you use, and how much ventilation they have.

Feeding

Mice need to be fed and watered every day. A plastic or glass water bottle can be hung through bars into the cage, or attached inside the tank using either a bottle holder or sticky-back velcro strips. Mice need access to a source of water at all times. Bowls are generally not recommended. Mice will kick bedding into the water or foul it with waste in very short order. They dehydrate very quickly and a day with no water for a mouse can be a death sentence. If you find your mouse is behaving oddly or looking off, the first thing you should do is make absolutely sure the water bottle is working.

Mice have many commercially-available foods designed for them, and some owners choose to mix their own feed. Commercially-available food comes in either pelletized (often called lab block) or seed mixes. Feed mixes for breeding animals need to have a higher protein percentage than feed mixes for pet animals. Some breeders use small amounts of kibble designed for cats or dogs in addition to the mouse’s regular feed in order to increase protein consumption.

Avoid feeds that list hamsters, gerbils, or other rodents on the package, though mice and rats can usually eat the same foods. In general, a mouse’s digestive tract is geared toward grain seeds like oats, wheat, and barley, with a little seed like flax, pumpkin, or sunflower and occasional bugs for protein, particularly mealworms. Homemade mouse mixes that contain mostly these kinds of foods do well to provide for a mouse’s diet. Be wary of those that include large amounts of seeds or human foods.

The majority of breeders do use pelletized foods like Native Earth or Harlan Teklad, and the breeder of your mice can give you more information about what that line of mice will be used to.

Enrichment

The last thing a mouse needs to get by is a source of enrichment. Even laboratories accept that mice need an enclosed shelter inside their caging to use as their nest. Anything from a purpose-made little igloo to an empty tissue box with the plastic removed will do just fine. Mice do love to shred cardboard, so cardpaper boxes and tubes are a favorite. The cardboard provides a hiding place until it is shredded into little pieces of nesting.

In addition to their house and a tube, some mouse breeders and owners include a wheel for exercise, especially for lone males. Wheels advertised for mice are almost always too small, so see how large a wheel you can fit into the cage. A too-small wheel causes a mouse to develop “wheel tail” in which the tail is permanently and painfully curled up over the mouse’s back.

Metal wheels can be squeaky and difficult to clean, while plastic wheels tend to accumulate urine build-up and can be chewed. Wheels with bars can trap the feet or tails, causing injury, and mesh wheels or solid plastic wheels are a way to avoid this.

Saucer-type wheels, in which the mouse runs atop a spinning disc instead of inside a wheel are an excellent way to avoid wheel tail or injury while using very little space. They are very safe. There is also a mouse hut designed with a saucer wheel on the roof, often used in laboratory cages which have a premium on space.

Other forms of enrichment like branches, ladders, and other places for mice to climb or hide can add more interest to the cage. Always be careful about toxicity of things not designed for mice, especially if they came from outside. Fruit wood and oak are generally safe, as are items designed for birds. Items designed for reptiles and fish are often safe, though soft plastic plants are quickly destroyed. Any kind of thready fabric can be a danger, as loose threads can wrap around small limbs and cause injury. Thread-less fabrics like fleece are much safer, and some owners keep hammocks or other fabric toys in their mouse cages.

Breeding

There are many reasons you might want to breed your mice, whether you want to show, to create more pets for yourself or others, to learn about genetics, or to produce feeder animals for other pets. Each of these has very different methods, but the general facts of mouse reproduction and methodology remain the same.

A female mouse (hereafter called a doe) goes into estrus and is fertile every five days. Breeders generally wait until the mouse is 8-12 weeks old, generally erring on the later end of that range, to pair their does with a male mouse (hereafter called a buck). Bucks are fertile by 28 days old, and generally live alone after that. Bucks will fight to the death, especially over a doe.

Bucks left to live with their pregnant does will impregnate the doe again as soon as she gives birth. Bucks removed up to several days prior have managed to cause back-to-back litters because sperm can survive in the uterine environment for some time, making a solid “due date” an unlikely prospect. Back-to-back litters can be very difficult for the doe and her pups, and so these are discouraged.

Pregnancy lasts 19-21 days, at which time an average of ten pups are born. Litters can be as small as a single pup or as large as two dozen. Does have ten teats, though smaller litters grow more quickly and more healthily than larger ones. Maximum milk production per baby mouse is achieved at a litter size of three, with litters over six seeing a decrease in milk availability.

Buck pups are weaned at 28 days to prevent them from impregnating their mothers, while does are generally left with their mothers until six weeks. Bucks are fertile generally until they die, while does can start to lose fertility by 9 months, with litters after 1 year increasingly dangerous. Because does do not have menopause, they can still get pregnant well after it is healthy or safe for them to do so, and these litters tend to be very taxing or fatal.

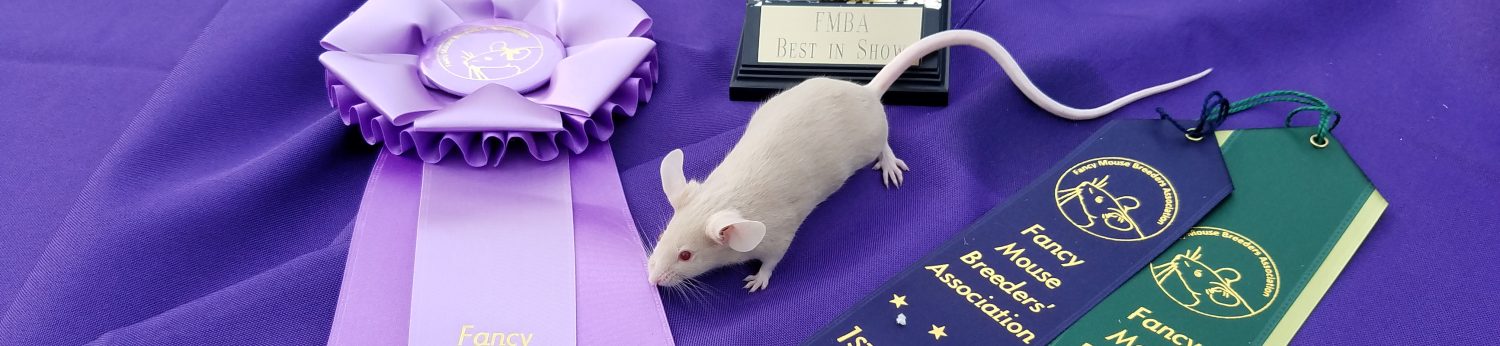

Showing

Not all mice fit well into a specific show variety, and the list of varieties varies from club to club. Every show variety has a standard specific to that variety at that club, and mice bred for exhibition are held to that standard. The overwhelming majority of mice at a show are entered by their breeders, with showing of mice acquired from others being generally discouraged though not disallowed, so long as the mice are properly identified. Show mice are generally very inbred, larger, and “typier” than mice bred for pets or feeders. The inbreeding of mice is generally accepted as a method to find and eliminate harmful genetic traits. Size is selected for in most varieties, with the pale selfs being the largest mice, and coated mice or marked being generally being the smallest. Both does and bucks are shown, though the standards generally fit better to a doe’s build. Type is a standard describing the shape of a mouse’s body, very similar to conformation show in dogs or cats. Mice are generally expected to have long, racy bodies with long, thick tails well set at the base, an arched loin, large and well-shaped ears, and a wedge-shaped head with large eyes. Type, like size, is greatest in pale selfs, with coated and marked classes having very little.